Last post I introduced the big question –

“Are doctors going to be replaced by computers soon?”

We also saw one possible answer: “Yes”, which we are going to investigate in this series of articles. Over the next few posts we will start building a foundation for answering this question, by defining and exploring some of the basic concepts.

I want to start by talking about medicine as it relates to automation. To understand if automation is possible, we need to understand the medical process. In particular, we need to know what is going on in the heads of doctors, since that is what we want to replicate or improve upon.

Standard disclaimer: these posts are aimed at a broad audience including layfolk, machine learning experts, doctors and others. Experts will likely feel that my treatment of their discipline is fairly superficial, but will hopefully find a lot of interesting a new ideas outside of their domains. That said, if there are any errors please let me know so I can make corrections.

What is medicine?

Dr Gross would say medicine is a way to make you more special, with just a little help.

First up, we are mainly talking about diagnostic medicine. Autonomous robots exist, but they aren’t ready to perform surgery. I’m personally super excited by the advances in robotics in recent years, but even folding clothes and opening doors at a five year old level is a fair way off 🙂

Diagnostic medicine is the mostly non-physical part of being a doctor. Diagnosis and treatment choices, with a few other elements. When most people think “diagnostic medicine”, they probably think of Gregory House, MD. The super-smart Sherlock Holmes character who thinks really hard about a problem to solve it. These people are usually characterised by having vast knowledge, amazing intuition and poor social skills.

This isn’t medicine. Or more accurately, it is a tiny part of medicine.

The vast majority of medical practice isn’t knowledge-based at all.

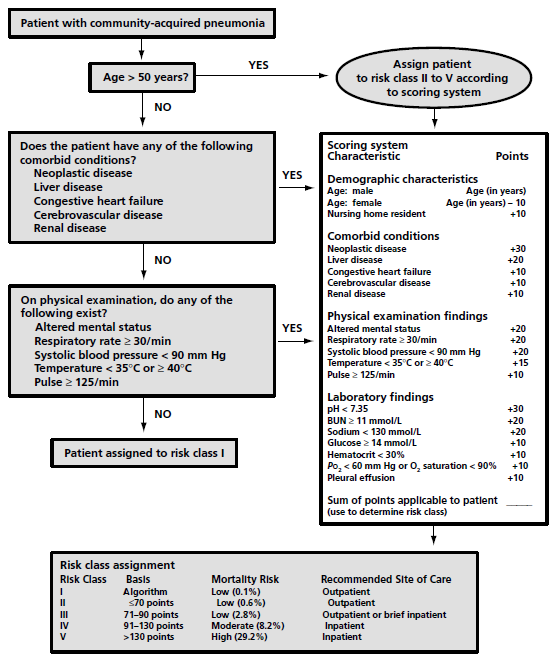

Story time! Decades ago everyone thought being a medical expert was about knowledge, and computer scientists tried to automate the knowledge base of medicine. The earliest computer system that outperformed doctors was MYCIN, an AI system that was developed in Stanford in the mid 1970s. It was knowledge based, codifying the process of identifying the likely cause of infection and choosing a treatment for it in a set of 600 rules. For to doctors reading this, these rules are the same as a flowchart based treatment guideline. For example, a guideline for pneumonia assessment:

To turn this into a computer program, like MYCIN, the flowchart is converted into bunch of nested if/then statements, like:

if community acquired pneumonia

> if age greater than 50 yrs

>> then apply scoring system

> if patient has comorbidities (x, y, z)

…

There was more to MYCIN, but that was the core of how it worked. With the benefit of 40 years of post-MYCIN experience, we can say a couple of things about it:

- MYCIN worked really well. The system identified an acceptable therapy more often than the infectious diseases experts that they compared it with.

- MYCIN was never used in clinical practice.

The standard explanation for this failure to make a clinical impact was that MYCIN required time-consuming manual data input and that the IT infrastructure didn’t exist in the 70s to make use of it. But this argument isn’t very satisfying, because those challenges have long been solved. We can automatically mine electronic health records for phrases or keywords to populate our systems, and we certainly aren’t bottlenecked by computation or electronic infrastructure anymore. But we still don’t use MYCIN, or almost any of its successors.

To understand my take on the clinical failure of MYCIN, imagine going to the doctor for a cough. Your doctor asks you some questions, listens to your chest, takes your temperature and your pulse rate. They send off a sputum sample or blood test. They might even get a chest x-ray. And after all that, how long does it take them to decide on an antibiotic?

Seconds, probably. Most doctors would barely register the decision as a conscious choice.

The fact is, the knowledge and decision making part of medicine becomes automatic for doctors. There is a long history of cognitive science research in medicine (I personally think this seminal paper is required reading for anyone that wants to understand medical expertise) and it shows that senior doctors don’t really think about many of their decisions. They engage in an experience based form of pattern matching. In fact, senior doctors often perform worse if you slow them down and force them to think.

Thinking really hard is a romantic notion, but isn’t actually a part of most jobs.

This phenomenon certainly isn’t limited to doctors, as the literature on expertise reveals more generally. Improved rapid pattern matching is thought to account for the performance differences between chess grandmasters and lesser experts (read page 10 and 11 of this book), as well as expertise in numerous other domains (music, sport, writing and so on). As stated in a more recent review paper

“Rapid pattern recognition … is characteristic of experts in both perceptual and richly symbolic domains.”

For the doctors who are a bit put off by that characterisation of medicine, let me frame it another way; Medicine is as much an art as a science. We’ve all heard that before, and it sounds good, right? In fact, it is often used as a defense against predictions of automation (like in the top comment of this reddit thread, or in the many articles by doctors arguing that automation is unlikely). I agree with the statement, but I think it has been significantly misinterpreted.

When we say “medicine is an art”, we mean that some parts of the process are ill-defined and can’t be written down or codified. That is what “a science” is; a set of reliable well-defined rules. In medicine our gut is often just as useful as our knowledge. We see a patient and we just know what is wrong with them. We get a sudden burst of inspiration and diagnose a rare disorder we hadn’t considered. We get the feeling our patient is about to crash for no identifiable reason.

That is what subconscious pattern matching feels like from the inside. Your brain compares your patient against your experience, and returns a “best match” answer. Without your conscious thought, and without needing you to invest much time.

The key point here is that the part of the medical process that MYCIN automated had a negligible cost (measured in time spent). Saving time on a process that takes between seconds and minutes just isn’t worth the effort of overhauling our current systems.

But all of this does raise an interesting question: what are diagnostic doctors spending all their time on, if not “thinking”?

Perception.

They are looking, listening, touching, and measuring. These are mostly sensory tasks (with less complicated motor control elements), and they take up a big portion of a doctor’s time. In fact, the largest disruption in modern healthcare history was due to the automation of perceptual (and minor motor control) processes – clinical chemistry services. Things like measuring electrolytes in serum. Between 1965 and now, one lab found that their workforce had decreased by about 25%, even as the volume of work significantly increased. This has resulted in an 80% reduction in the per-test cost for clinical chemistry, which is exactly the sort of outcome we are hoping for in medicine.

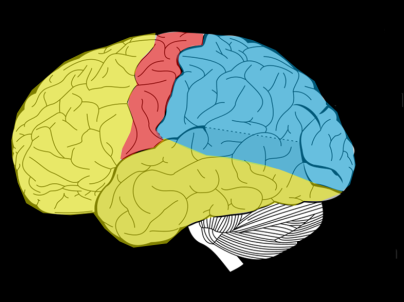

Biologically it seems obvious that perception is an important task. Almost half our “upper” brain is dedicated to sensory processing and integration. Everything else including planning, reasoning, moving, decision making, personality, morality, memory, all the other higher functions that distinguish humans from animals – is smooshed into the other half. Obviously, perception is a task worth spending our precious energy on.

Blue is sensory, and red is motor control. That’s a lot of processing for functions we generally think of as ‘easy’.

The major stumbling block for automating perceptual tasks, and the difference between clinical chemistry and medicine more broadly, is that most perceptual tasks are not amenable to simple physical solutions. Rather than just measuring voltage differences with ion-selective electrodes or counting the number of shadows that pass a laser beam (biochemistry and cell counting respectively), doctors need to see their patients.

For decades, machines were no good at this sort of “human-like” perception. Five year olds beat them by miles. So computer scientists solved other, more tractable problems. MYCIN asked a doctor to do all the perception and then automated the decision making. It was a problem that was solvable, but it wasn’t a problem that was valuable.

The revolution that is happening in artificial intelligence can be understood in one idea; deep learning is really good at human-like perception. In fact, deep learning systems now perform around human level in a wide range of perceptual tasks, like visual object recognition and voice transcription. And because perception has such a big role in expertise we are achieving superhuman performance in “expert tasks”, like driving cars or playing complex games like Go. It turns out that these tasks were all bottle-necked by perception, not decision making.

Machine learning guru Andrew Ng has a rule of thumb – “If a typical human can do it in 1 second, so can deep learning”. My experience in medical applications suggests a slight restatement of this rule:

“If an expert can perform a task in less than a few seconds, it can be automated.”

They key difference is that I have not noticed a distinction between the learnability of tasks that the “typical person” can do quickly, and tasks that medical experts perform via subconscious pattern matching (although I will explore this nuance in more depth another day).

To return to the idea that “medicine is an art”; if the art of medicine is integrating patient patterns and learning to make best use of that stored experience, then deep learning is automating the art rather than the science. Rather than a defense against automation, the art argument shows us why these techniques are more promising than previous approaches.

We can drive this home with an example. Take reading a chest CAT-scan in radiology, we can make a flowchart like this:

This is an actual diagnostic flowchart from this paper published in a high quality journal. You can see how it can be turned into a computer program quite easily, but the most important thing is that every blue box is a perceptual task. Each term used (like “tree-in-bud“, “bronchiectasis” and so on) are patterns you see in the images.

You should recognise right away that there are no other tasks to solve. If you can perceive the patterns, you have the answer.

This is why Prof Hinton was talking about radiology in his medpocalyptic predictions. The two medical specialties generally considered most “at risk” are diagnostic radiology (my job!) and pathology, and both are almost entirely perceptual (finding patterns in medical scans and microscope slides respectively).

The next obvious question is: how big are the “at-risk” specialities? How much of medical expenditure is perceptual in nature, and therefore potentially solvable by deep learning?

These specialties are huge.

I leave it to readers to decide what or who an Ass. at Ops might be 🙂

Diagnostic Imaging (DI) and Pathology make up over a quarter of our total health budget (which in Australia is around 10% of GDP). In DI, about half of that cost is wages. So even if we just limit ourselves to those two specialties, that is something like 1% of national GDP in wages. Quite staggering.

Other fields commonly thought of as “at-risk” include dermatology and ophthalmology (for the “looking at the skin” and “looking in the eyes” components), but these are much smaller slices of the pie.

It is worth noting, however, that many other medical specialties have large perceptual components. Your local family doctor still spends a lot of time looking, listening and feeling. A surgical specialist does too, and relies a lot on radiology and pathology tests. A psychiatrist learns a lot from sight and sound.

So we might be looking at a technology that can do parts of the work of most types of doctors, even if it can’t replace all of the jobs. And that leads us to the topic of the next blog post – understanding what we actually mean by “automation”.

See you next week 🙂

Previous posts

Next post: Understanding Automation

Another great post, thanks! I’m excited which thoughts you might cover in next week’s and if you are going to tackle the “clinical” disciplines of medicine as well.

LikeLike

Thanks very much!

I’ll be discussing the various specialites in a bit more detail next week I think, I’ll see how much I can fit in.

LikeLike

Great post!! Just wanted to share our most recent publication for diagnostic inferencing: https://aaai.org/ocs/index.php/AAAI/AAAI17/paper/view/14223 .

LikeLike

Great post, Luke, thanks for sharing!

Question: What is your pick for the #1 problem/task in medicine that’s (at least partially) solvable by Deep Learning but where you are not seeing a lot of focus from the DL community?

LikeLike

That is a hard question because so many people are working on things now. Any task I mention is probably already being solved.

I personally think there is a big scope for the automation of video based assessment via telemedicine. We can pick up a lot via visual and audio cues, so we relieve a lot of pressure from our health systems with some sort of smart triage service (even redirecting ten or twenty percent of patients would be massive).

The problem is we have no datasets for this. I’d love if someone was trying to build them though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the response, Luke. Good point about the absence of telemedicine datasets.

LikeLike

Great post! One complaint, though… I can’t see the links! I’m using Chrome and I’m R-G colorblind, and for me the links are indistinguishable from the rest of the text.

LikeLike

College students pursuing a Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Mathematics may select

from 4 options: Mathematics, Mathematics Training, Statistics, and Actuarial Science https://math-problem-solver.com/ .

Direct and semi-direct merchandise of groups; quotient/issue teams; isomorphism theorems.

LikeLike